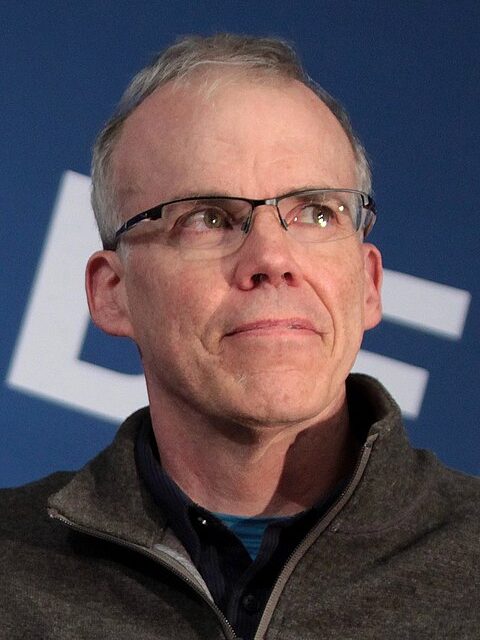

Author Bill McKibben talks about the hope of a solar energy future and a chance to heal the planet as he discusses his new book, Here Comes the Sun: A Last Chance for the Climate and a Fresh Chance for Civilization.

Transcript:

Rachel: I’m here on Talk of the Bay with Bill McKibben. He has a brand new book out called, here Comes The Sun, A Last Chance For The Climate and a Fresh Chance For Civilization.

A provocative title from an author who has relentlessly pushed the idea that we can. Deal with the climate crisis if we act soon. Bill, what’s different about this book than your previous book seems to be a little bit more optimism, but also increased urgency. How do you balance those two things in this book?

Balancing Optimism and Urgency in Climate Action

McKibben: Well, that’s, it’s, you’re definitely right. Um, we live at a. A very fraught moment. Uh, the things that I’ve been warning about since I wrote the first book about climate change, what we then called the Greenhouse Effect back in the 1980s. Those things are coming true, and they’re coming true with flood and fire and disaster of all kinds at precisely the moment that our democracy is under enormous threat.

And part of that has been an assault on clean energy. So there’s a lot of. Big, bad things happening, I think, on our planet and in our country. But the big good thing that’s happening, uh, and it’s really flying under the radar some, is this super rapid spread of energy from the sun. The last 36 months or so have been just.

Unlike anything that’s ever come before. This is not only the fastest growing energy source on the planet, it’s the fastest growing energy source in the history of the planet. And it’s starting in the places that are taking it really seriously to transform the human relationship with energy. Uh, California is obviously one example.

Uh, most days now California supplies a hundred percent of the electricity that it uses from renewable sources for. Long sections of the day at night. California supplies often its biggest supplier from the grid is now batteries that have been soaking up excess sunshine all afternoon, and as a result, California fourth largest economy on Earth is using about 40% less natural gas to make electricity than it was two years ago.

California’s Progress in Renewable Energy

That’s the kind of change that if we manage to spread it around the world. Quickly, uh, that would knock tenths of a degree off how hot this planet’s eventually going to get. It’s the single most encouraging statistic I’ve come across in almost 40 years of doing this work.

Rachel: That’s wonderful. I, I was left with so many questions.

McKibben: I’ll try to get to them all, but one big one of course is can the current politics of our country, one of the biggest polluters of carbon into the atmosphere? Can politics stop this market force that seems to be making it cheaper and cheaper? It can’t stop the market force, but it may be able to use politics to get in the way, uh, enough to really slow things down in the us you know, the federal government is now just doing one, I think, insanely stupid thing after another.

For instance, they’ve put federal lands off limits for solar and wind, um, but full speed ahead with coal and gas and oil there now. Adding new subsidies to coal in this country. They’re trying to kill off the electric vehicle, uh, uh, progress that we’ve started to make, um, under President Biden, on and on and on.

This can slow things down here at a crucial time, but it is worth remembering that. The US is, at this point, only about 11% of the emissions on the planet. They can’t slow down what’s happening in the rest of the world. In fact, I think that all of Trump’s, uh, talk of energy dominance and how the US is going to be in charge, I think that’s scaring lots of other countries into moving even more quickly on renewable energy.

I, I don’t think there’s many people who want to depend on, uh, a increasingly fickle and erratic us for their supplies of energy. So people are turning, uh, instead to China and to their mastery of this new technology. Well, I was very encouraged to read about balcony solar. This is like the most, uh, disseminated form of energy that people are literally putting little solar cells on their apartment balconies all over the world.

The Rise of Balcony Solar and Distributed Energy

Rachel: This is ’cause it’s cheaper. Right?

McKibben: Exactly. This has happened full scale in Europe in the last two years. There’s now. Uh, millions, several million Germans who have gone to whatever the German Best Buy is and come home with a solar panel for a few hundred euros that is designed to be hung from the railing na vere veranda and plugged straight into the wall.

Uh, in many cases, they’re producing 20% of the energy that they use. Uh, that’s illegal everywhere in this country except. As of two months ago in that progressive Bastion, Utah, where the state legislature passed, enabling legislation by a unanimous vote because some libertarian minded state senators stood up and said, why can the people of Hamburg and Frankfurt access this new miracle, but not the people of Provo and Salt Lake City?

So now if you go on YouTube, you can find lots of videos of people building, uh, uh. Doing just this kinda work in, in Utah, and hopefully we can get that to spread. That’s one of the modest goals of this Sun Day, uh, uh, national Day of Action that we have coming up on September 21st, uh, the fall equinox, that people can find out what’s happening in their community at Sunday Earth.

Rachel: Yes, I’m looking forward to that. And we’re gonna do an interview about the local organizing for that here in the Monterey Bay area. I wanted to, um, address one thing that’s always confused me and maybe confused our listeners as well, which is we hear a lot about the percentage of solar versus, you know, petro energy.

Um, but isn’t it also important to bring down the total output of energy in general of. Petro to get up with our goals. Yes. Um, so it’s not just a percentage. If you have, you know, bitcoin and chat GPT eating up massive amounts of use, you haven’t really brought down the total. So can you talk about the difference between percentage and total?

Energy Consumption and Efficiency

McKibben: Yes. And it’s a very good point, but that’s why that number that I gave you from California is so astonishing using 40% less natural gas to generate electricity than. Two years ago, uh, and we can see the same thing starting to happen in other places around the world. Uh, the story that really blew my mind was what was happening in Pakistan right next to China.

And so easy to get cheap Chinese solar panels across the border last year. Individual Pakistanis, and you can go on Google Earth and look at yourself, have transformed the. Uh, power grid in that country by putting solar panels on every flat surface in Lahore and Karachi and Islamabad. Uh, um, they, they built the equivalent of half the country’s national electric grid in about eight months.

The earliest adopters and most fervent adopters were farmers who. Wanted to replace the diesel that they were using to run the pumps that, uh, that allowed them to irrigate that diesel was often their biggest cost input. So they went, started buying these cheap solar panels .They often lack the money to build the steel supports that we see, uh, so commonly.

Instead, they were just laying them on the ground and pointing them at the sun. But Pakistan last year used 35% less diesel than they did the year before. We should definitely be trying to. Be efficient with energy. And one of the good things about the move to electric, to EVs to, uh, heat pumps instead of furnaces that kind of thing, is that they use a lot less energy because they’re using it much more efficiently.

Global Adoption and Competition

They don’t produce the same kind of waste heat. That is what happens to most of the fuel that you burn in the tank of your car.

Rachel: And does the extreme heat, which you mentioned Pakistan is one of the hottest places. Is heating up the fastest, does extreme heat impact solar panels efficiency?

McKibben: Not very much.

Rachel: okay. Good to know. Yeah. And so we’re in kind of the context you said at the beginning is, this is really good news. I felt like in a way I was on the Giant Dipper rollercoaster, um, going up and down as I read your book, but on the good news, on the bad news, yes. But the good news is that. If this does speed up like it is, um, we could seriously have a decentralized, uh, system that didn’t skew our politics toward the big oil interest, which really, you know, got my heart racing ’cause it well gave me a sense of hope that we could have this.

And then there’s the other side, which is climate change is proceeding without much abatement still. And there’s these tipping points staring us in the face. So we’re kind of in this existential race. Yes. And you say, we can’t just wait for market forces to get us there. So talk more about that context piece.

McKibben:I sure will. Um, so let’s talk about the climate part first. We have to speed up here. Um, go even faster than this transition is, which is currently mostly being driven by economics. We need it also to be driven by political concern because climate change is happening so fast. Um, you all are well aware of just how.

Just how fast that’s happening, um, because you can see the results in California all the time, but. The most systemic, you know, um, uses around the world. The most systemic systems around the world are really starting to falter in dangerous and scary ways. The way that the Jet stream works, the way that the Gulf Stream works, these are now eroding in real time.

So we have to move fast. But if we move fast, we not only help. Ameliorate some of global warming, not stop it much too late for that, maybe cut some tenths of a degree off how hot the planet gets. Not only do we get that benefit, and not only do we get big reductions in pollution because 9 million human beings, one death in five comes from breathing the combustion byproducts of fossil fuel.

But we also get. This other thing that you were alluding to, which is this geopolitical bonus, think about. How different the geopolitics of the world over the last 70 years would’ve been if oil was inconsequential. Um, think about how many fewer wars and coups and on and on we would’ve had to be. Engaged in if we ran the planet on a resource that’s available to everybody, everywhere all the time.

Uh, human beings are good at figuring out reasons to fight wars, but even human beings are gonna struggle to figure out how to fight one over sunshine. Hmm. I like that, that, that it’s something available to people who don’t have a lot of money and, um, that. That we can speed this up with the right policies.

Rachel: Is it possible that this could all happen without the United States for the next five years or so? Yeah, it’s possible that the US could, I mean, the us uh, the US could be, uh. One, one possible outcome here is that 15 years from now, the US will be a museum where people from around the world travel to gaw at how people lived in the olden days.

You know, um, uh, uh, a kind of colonial Williamsburg of the internal combustion era. Oh my gosh. Um, what a way to think of it. Yeah. I hope that doesn’t happen. I think in the very short run, um, with Washington in the hands of the oil industry for the moment, the US is going to be doing everything it can to slow down this transition.

But I think globally that may have the odd effect of actually speeding it up some, um, ask yourself. You know, Donald Trump has talked a lot about energy dominance and how he wants all the other countries in the world, depending on the US, for their supply of oil and natural gas. If you’re the ruler of some.

Asian country. Uh, you look around and you ask yourself, do I really want to depend on the supply of something as important as energy on the fickle and erratic government of the United States? Uh, Indonesia announced last week plans to build out a hundred gigawatts of solar power by 2030, uh, which would.

Leave it second only to China, I think in the scale of their, uh, commitment. Um, that’s the kind of thing that I think we’ll see more and more and more of, uh, especially as all the other technologies that make use of that electricity spread around the world. We’re used to thinking that cars come from Detroit, but.

Uh, at the moment, the biggest builders of cars in the world and the biggest exporters are gonna be in China because they’re producing EVs at very low cost that have extraordinary performance characteristics. And everybody across the developing world is suddenly buying them if they’re buying cars at all.

Rachel: Uh, uh, because they’re better and cheaper and Right. I think a lot of us would buy one if we could. Um, they say they were. $10,000. Right. For an electric vehicle. Absolutely. Absolutely. And so if you’re, I mean, if we’d buy ’em, if we could think about if you’re an Ethiopian or a Brazilian or what, whatever, that’s what’s happening and, and that means that the demand for oil.

Five years out is going to be much smaller than people had been assuming even a few years ago. Half the cars sold in China last month came with a plug hanging out the back. Uh, those are cars that are not ever going to be buying oil, you know. Yeah, I wanna talk about the difference between giant solar farms that you see, uh, you know, in the California desert.

Rachel: Mm-hmm. Yeah. And, uh, home systems. And whether you think, um, both of those are part of the solution you’re describing, or whether these giant solar farms also. Concentrate power literally in the hands of a few. No, we need both. And California’s done a better job with the giant solar farms than with the rooftop ones.

Large Scale vs. Distributed Solar

Governor Newsom’s done a couple of dumb things about rooftop solar in the last few years, um, and which is too bad because we need both. You can get a lot of power out of the Mojave from those big solar farms, and that’s good because California uses a lot of power. But the power from people’s rooftops is particularly valuable, um, in part because we now know how to sort of string it together.

Um, the California ran a test a couple of weeks ago of what they’re calling virtual power plant, and they hooked together a hundred thousand batteries in people’s homes across California and dispatch that power to the grid. And, and found that it was the equivalent of having a pretty big power plant come suddenly online.

Um, that’s remarkably useful power ’cause it’s not like everybody’s home is suddenly going to, you know, uh, uh, have some maintenance outage or something the way that power plants do. In fact, when we get to the point in this country that we run our whole vehicle fleet on EVs, the batteries of those electric vehicles will be enough.

Provide enough power to run the entire country for about two days by themselves. So the possibilities here, now that we have access to clean, cheap. Solar energy and the batteries to store it also getting cheaper and cheaper. It’s remarkable. And the place that’s learned the lesson from California is Texas, which is now installing this stuff even faster than the Golden State.

Rachel: What is it that’s caused these panels to come down so fast? What is the main driver of the cheaper solar panel?

McKibben: Human intelligence. Human intelligence, this is, this is not like oil or gas or coal, which are essentially commodities. Um, when you’re buying a solar panel, which you’re basically buying is.

Human intelligence that informs it, and this we get better and better and better and better at this. There’s a very steep learning curve. The price keeps dropping at the moment. Every time we double the amount of solar on the planet, the price drops by about another half, and there seems to be no end in sight to that.

Trend. Um, and, and just that it, you know, some point earlier this decade that crossed an invisible line where it became cheaper than burning coal and gas and oil. We live on a planet where the cheapest way to make power is to point a sheet of glass at the sun. That’s an amazing miracle. It’s a miracle that hasn’t sunk in yet.

I think in most of our heads, because we’re so used to thinking about this stuff as alternative energy. Uh, uh, that’s the kind of ghetto we’ve put it in in our minds. You know, in food terms, we think of it as like the whole foods of energy. Nice, but pricey. And we also look at like pg and e, which is our big, you know, monopoly.

Uh, we look at them as, you know, kind of with. Angst and anger, but that we have no choice but to use them, right? And that we have to wait till they hook us back up when there’s a storm. So we’re very much beholden increasingly to this giant corporation. So increasingly people are figuring out how to be less, much less beholden.

That’s what the solar panels on your roof and the battery in your basement do. Um, and, and that’s, you know. That’s why places like pg e are gonna have to come to terms with this. ’cause if they don’t, it’s only a matter of time before a lot of people opt out altogether and just go off grid. That’s how good the technology and how cheap it’s getting.

Permitting and Implementation Challenges

Um, but it would be much easier to do this and this will be one of the focuses of Sunday. If it was easier to, uh, get this stuff up on your roof. Uh, we have a. Bizarre and Byzantine permitting system in this country, um, that often means it takes months between your decision to put solar panels on the roof and actually hooking them up and connecting them to the utility.

In a place like Australia or the eu, that takes not months, but days. I mean, you can order solar panels on Monday and by Friday have them. Churning power out on your roof. Um, largely because they’ve figured out how to do this kind of automated permitting system and happily, there’s not, like it’s produced a spate of rooftop solar fires across Australia.

Mm-hmm. It’s a safe technology. It shouldn’t be harder than putting a new refrigerator in your kitchen. Um, um, but we have to. Push hard to make that happen. California has actually passed a law mandating that, uh, communities use, uh, uh, uh, sort of instant permitting, um, uh, series of apps that allow contractors to get an instant permit.

But it takes a while for communities to roll that out. Uh, Sunday, one of our tasks is to speed that up. That’s a great idea.

Rachel: You know, I thought your discussion about the economics of solar was fascinating because you kind of tried to answer the question, why is China the one leading all of this? Because solar, you know, the other forms of energy like petrochemical, petro energy, um, yields profits because it costs less.

In one sense to pull it out of the ground and then you sell it for higher and then you sell it again when you refine it, uh, as gasoline. But in this case, solar doesn’t like, give you massive immediate profits. So, um, the investment of China is interesting ’cause their government can kind of overlook that.

But in our country it seems like. There isn’t a lot of investment because there’s not a lot of return, and that’s the old capitalist system, counting it in quarterly increments. Right? Yeah. Can you talk a little bit about this and maybe demystify. Yes. How the investment part of this works, does it have to be public?

McKibben: The CEO of Exxon said last year, we’re never gonna invest in renewables because they don’t offer, as he put it above average returns for investors. And that’s true if you think about it. Uh. The reason that the oil companies don’t like renewable energy is because their business model has been to get all of us to write a check every month or every trip to the filling station, whatever, for a, a, a, a new tank of oil.

Um, but the sun. Delivers energy for free. Once you’ve set up the panels, that’s good for everybody who doesn’t own a coal mine or an oil well or whatever the problem is getting that initial investment to get the solar panels up. That’s why Joe Biden did this big IRA program that was designed to do that over the next decade.

It’s now been. Cut off by the Republican Congress, the tax credits will expire at the end of the year. Uh, and that is gonna slow down that process here, but I think it won’t stop it or even close to stopping it just because, as I say, the economic get better with each passing month. Um, and, and. Though Exxon et all can do a lot to control our national political system with the cash they have, um, they can’t really control that.

Eventually people are gonna start noticing that other countries are able to produce their energy more cheaply, and that’s going to give them a huge comparative advantage in. Everything going forward, it’s as if we’re taxing ourselves by not allowing the spread of this clean energy to happen. Um, I as a patriot, you know, it makes me exceptionally Annoyed. The solar cell was invented in the us so was the lithium ion battery, and now we’re just handing them over to Beijing. Uh, you know, it’s, you could say they’re eating our lunch, but it would be more accurate to say we’ve set a, you know, red capped crew of waiters over to China to serve the lunch up for them.

Environmental Concerns and Land Use

Hmm. We couldn’t be doing anything to make life easier, uh, for Xi Jinping than what we’re doing here. I wanna talk about a couple more things before I let you go. One is, um, you know, objections to solar by people who claim to be environmentalists. Um, they’re worried about mining, you know that there’s more, uh, national sacrifice zones because we’re mining lithium or other rare earth minerals.

Then, you know, there’s also objections because of do we have enough land for Yes. All of these glass panels. So let’s, let’s take those two objections and, and look at them and how you dealt with them in your book. Those were both things that interested me a lot going in, um, because I am an environmentalist.

Um. So yeah, there’s no free lunch. Uh, there’s just less expensive and more expensive lunches. We do have to go mine some lithium, but if you think about that for a minute, you quickly figure out why that’s different. You mine some lithium, you put it in a battery there, it rests for a quarter century doing its work.

Uh, when the battery itself degrades, you can actually, and we actually now do recycle that lithium and just start all over again. If you go mine some coal, you set it on fire and have to go mine some more coal, uh, tomorrow. That’s why the Rocky Mountain Institute estimated last fall that you’d get all the.

Minerals that you needed for the, uh, energy transition by 2050 with about the same volume of mining as we used for coal last year. Hmm. Um, um, so yes, we should try to make mining as. Safe and environmentally sound as possible, but we should rejoice in the fact that we’re figuring out ways to do O over time.

Less of it. A way to think of this in your mind is a shipload full of solar panels sent to the us say, will over its lifetime, produce about 500 times as much energy as that same shipload full of coal Would that gives you some. Just sense of the change here. Yes, absolutely. As for land use, uh, we already use an enormous amount of land for oil and gas and coal.

Mark Jacobson at Stanford says probably the footprint won’t increase much as we’re, uh, using sun and wind instead. But what’s different is this footprint is much more benign. Um, you know, um. If you put up solar panels in a farm field, say, uh, one of the things you’re doing is taking what’s currently a biological desert, often the cornfield in the US and that’s our biggest crop.

Is sprayed within an inch of its life. You, you, you’re replacing that with a field where, uh, large parts in between the rows are now, uh, possible for all kinds of interesting experiments. This field of voltaics is growing very fast. Because people are finding that in an overheated world, shade is a welcome commodity, uh, of interest to, uh, good Californians.

Uh, there was a series of studies in the last six months from France showing that the yield of wine grapes was up as much as 60% in, uh, uh, in fuels with solar panels. ’cause they’re providing some shade and retaining some moisture, uh, uh, in those places. Um, in Vermont where I live, we’re increasingly inter planting the rows of solar panels with, uh, pollinator friendly native plant plantings that are bringing in huge numbers of native insects and in return the surrounding farmers in their orchards and things are saying that fruit set is up 30 or 40%.

So there are lots and lots of. Uh, interesting ways to use these technologies, uh, uh, to take us away from the heavy, huge scale, uh, uh, monoculture industrial agriculture that we’re using at the moment. Um, we need clean electrons. It’s a perfectly good use of land to grow that crop. Uh, I’m speaking with Bill McKibben in his new book.

Rachel: Here Comes The Sun, uh, extols, the Virtues of Solar Energy for our Future. You say a lot of liberals don’t like solar panels ’cause of the way they look. Um, and also wind has become, you know, a battle between NIMBYs and NIMBYs. Um. Is there, uh, also a change that you’d like to see in the attitude of people who are looking at these things and saying they’d rather look at a cornfield than a solar panel?

McKibben: So some of it’s just education of the kind I’ve been doing to help them understand that, uh, uh, cornfield is, uh, less pristine and this is more interesting. Um, but part of it is just. I just wrote a long piece for Mother Jones saying, time for, you know, people like me, old white people to stop suing because there’s something they don’t like the look of.

Um, we’re in an emergency. Uh, our kids and grandkids are gonna have to deal with the world that we’re living, we’re leaving them. Anything we can do to speed up the transition and lower the temperature is a great gift to them, and it’s entirely selfish. To just keep saying, uh, I don’t wanna look at a solar panel.

Uh, change your aesthetic a little bit and understand it as a kind of beautiful, deep connection between human beings and our local star, which already gives us warmth and light and photosynthesis, and now is willing to provide us with all the power we could ever want. What a beautiful sentiment. I really appreciate this book.

Rachel: Is there anything that I didn’t ask you that you would like to say in closing?

McKibben: No, just that I’m looking forward to seeing pictures from all around the country on September 21st. Go to Sunday Earth and figure out how to take part in this big festival. Fantastic. Bill McKibben, I thank you for your book. I thank you for your time and all of the things you’ve done over the years to raise awareness about climate change.

Rachel: Thank you so much.

McKibben: Well, thank you. What a pleasure to talk, Rachel and um, and good luck going forward. Thank you.